By Elise DeYoung

Let’s examine the purpose and process of the Electoral College. For several decades, there has been a simmering debate over whether or not we should abolish the Electoral College. Especially since the 2000 and 2016 elections, when the Electoral College elected President Bush and then President Trump despite losing the popular vote, this debate has become increasingly mainstream.

In fact, a clear majority of Americans support replacing the Electoral College with a popular vote, according to a study conducted by the Pew Research Center.

However, before we can even consider abolishing our system of presidential elections, we must be sure that we understand its process and purpose.

The Process of the Electoral College

The US presidential elections have two stages: the primary and the general. You can find more information about the primary here. The general election commences once each party has chosen a nominee at the conclusion of the primary.

Similar to the primary system, the general election is composed of three rounds:

- The Campaign

- The People’s Vote

- The Electoral College

The Campaign

Campaigning during the general election is different than the primary since voters are now familiar with the candidates. However, this is still an essential aspect of the process since it’s the candidates’ final chance to persuade the public.

So, once more, they perform interviews, participate in political debates, and present speeches to maintain the support of their political base and persuade others of their position to win states.

The People’s Vote

As established in the Constitution, the people’s vote officially takes place on the Tuesday following the first Monday of November.

The standard voting method, in general, is very similar to the primary voting system. Americans gather at the ballot boxes to cast their vote individually. In addition, the concepts of “early voting” and “mail-in ballots” have been introduced in recent decades. No matter how you vote, election officials count the votes at the end of the Tuesday following the first Monday of November.

If you want to learn more about the voting laws in your state, read an article by USA Facts, How Do Voting Laws Differ by State? or refer to your state constitution.

However, the people’s vote does not determine the result of the general election. This is because American elections are not conducted by a popular voting system. Rather, the founders designed a system called the Electoral College.

The Electoral College

Briefly put, the Electoral College comprises electors from all fifty states that convene every election year to cast their votes, directly electing the President.

Who are these electors?

The Constitution provides only two stipulations when it comes to the electors. Article II, Section One, Clause Two states that an elector may not hold another office of Trust in the U.S. government. Furthermore, Section Three of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution says that no individual who has engaged in an insurrection may hold any office in the U.S. government, including the position of elector. Any further rules that apply to who can be an elector and how they are elected are left up to the states to decide.

How are the electors chosen?

The parties in the general election choose potential party-approved electors. Then, the people elect which electors they would like to represent them.

How many electors are in each state?

The number of electors in a state equals the number of Senators and Representatives in that state.

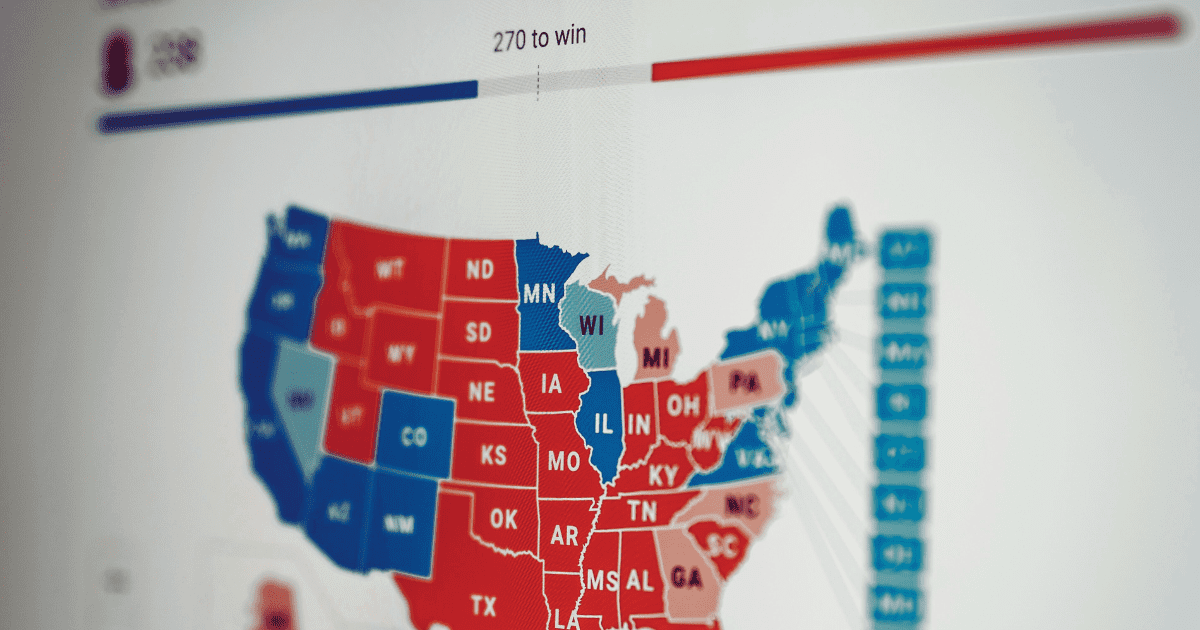

For example, Iowa has seven electors, while Wisconsin has ten, and Florida has twenty-seven. The Library of Congress has a country map showing the number of electors per state.

How many electoral votes are needed to win?

The winning candidate must receive at least 270 electoral votes, a clear majority. Suppose there is a tie, or the majority is too slim, which happened in the case of Thomas Jefferson versus Aaron Burr in 1801. In that case, Congress resolves the vote.

When does the Electoral College assemble to vote for the President?

They meet in mid-December after the popular vote has taken place. So, while we often celebrate or mourn the results of the people’s vote, the election is still not over for another month.

When the electors vote, do they have to vote in accordance with the popular vote?

The answer is the same as the delegates in the primary. Depending on the party and state they represent, some must align their vote with the results of the popular vote in their state. Others can vote for whomever they see fit.

The Process & Purpose of the Electoral College

This process is more complex than most election systems in other countries. Why did the Founders establish this system with so many steps when they could have established a popular vote?

There are two main reasons why the founders were wise to create the complex system of the Electoral College.

First, they rightly feared the tyranny of the majority. Alexander Hamilton said it well when he wrote, “The people is a great beast.” They knew that the people had to be controlled by a system that was out of their control.

“The people is a great beast.” —Alexander Hamilton

Second, the founders also knew that the federal government could not control the system that controlled the mob of the majority. An election system that was in the hands of the federal government could, and probably would, be manipulated by those in charge. They would secure power for themselves by silencing the people’s voices and disqualifying the opposition.

This is why the Constitution includes so many checks and balances. It distributes power among all fifty states rather than centralizing it in the office of the President alone, and why the Founders avoided settling for overly simple systems.

Electoral College—Still Relevant Today

The Electoral College is a firm institution that holds both the tyranny of the majority and the power of the government at bay. It does not allow for either of these groups to ultimately corrupt elections because neither group has the final say.

It is no surprise that those with political power do not like the system, it stops them from securing ultimate victory for their party. Neither is it surprising that the majority dislike the system, it doesn’t bow its knee to them. All in all, I would say that the Electoral College is doing exactly what it was designed to do.

And as the cliché saying goes, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Elise DeYoung is a Public Relations and Communications Associate and a Classical Conversations graduate. With CC, she strives to know God and make Him known in all aspects of her life. She is a servant of Christ, an avid reader, and a professional nap-taker. As she continues her journey towards the Celestial City, she is determined to gain wisdom and understanding wherever it can be found. Soli Deo gloria!