By Elise DeYoung

“Deeds survive the doers.” — Horace Mann

The origin of the public school system has all but been forgotten in the Western world. We seem to be under the impression that government schools have always been and always will be. However, a quick glance into history dismantles this ignorant idea. To understand the origin of government schools, we must examine a few basic questions:

- Who came up with the idea of government-run education?

- When was the first public school established?

- What is the goal of public education?

American citizens, specifically parents, deserve to know the answer to these simple contextual questions because, as Aristotle observed, before you can know what a thing is, you must understand what it was designed to do. So, what were the public schools designed to do?

Origin of Government Schools

The idea of government schools was first proposed by a man named Robert Owen. Owen was a utopian collectivist who wanted to use universal government education to condition populations to accept the conditions of communism. Sounds promising, right? If you are not familiar with Owen and his work, I encourage you to read Global Utopia and Government Schools.

Continuing down the timeline of public education, we then become acquainted with a man named Horace Mann. It is likely that you have a vague recollection of Mann, though he is not talked about nearly enough. You may remember him as the father of public education or the great public school evangelist. However, I would propose that history remembers Horace Mann for what he truly was—a cynical theorist and a hypocritical reformist.

Born in 1796 to a poor farming family in Franklin, Massachusetts, Mann was largely self-educated because he could only attend school six weeks out of the year. During his childhood, he applied himself to studies at the Franklin public library and eventually attended Brown University in 1816, where he graduated as valedictorian. In 1822, he furthered his studies at Litchfield Law School, and the following year, he practiced law in Dedham, Massachusetts. His career in law was short-lived because, in 1827, Mann ran and won an election for the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he would serve for six years.

When Horace Mann was elected to the Massachusetts State Senate in 1835, it became evident that he had a promising political career. With such a bright future ahead of him, Mann’s colleagues, friends, and family were shocked when he threw it all away in 1837 and turned his attention to radical education reform.

“Public Education is the cornerstone of our community and our democracy.”

— Horace Mann

The First Board of Education

Mann’s great ambition was to establish a nationwide, mandated, government-run, and controlled school system. He wrote, “Public Education is the cornerstone of our community and our democracy.” Some may counter that democracy is the cornerstone of our democracy, but regardless, Mann strongly believed that he would be the patriot to establish the American “cornerstone” of public education.

He quickly recognized, however, that before this could happen, these measures had to be executed on a local scale. In Massachusetts, there were a few publicly funded schools here and there (the first of which had been established in the 17th century by Puritans with legislation called the “Old Deluder Satan Law of 1647“), so Mann turned his attention to the creation of the first Board of Education. This he accomplished very rapidly in 1837, and that same year, Mann accepted the position of secretary to the Board.

The function of the Board of Education was to oversee all education in the state of Massachusetts. It was so well-liked by legislators and politicians that only thirty years later, President Andrew Johnson promoted it to the federal level and was given the official title “The Department of Education.” However, according to the Department’s history, only one short year later, it was demoted to an Office of Education “due to concern that the Department would exercise too much control over local schools.”

Happily for Horace, unhappily for the American people, it was reinstated by Congress in 1979. In 2024 alone, the Department’s budget was 90 billion dollars. With so many billions of dollars at its disposal, Americans should begin asking the question first posed by politicians in the 19th century: “Does the Department exercise too much control over local schools?”

This pressing question was clearly not a concern of Horace Mann because after establishing the Board of Education, his interest was piqued by the Prussian government, which had been actively imposing a universal government-run and controlled public school system for decades. What did this system look like? And could it be duplicated in the land of the free? In 1843, Mann traveled to Prussia to answer these questions.

The Prussian Model

In 1806, Frederick William III, King of Prussia, was defeated by Napoleon at the battle of Jena-Auestedt. In reaction to this embarrassing defeat, the Prussian elite blamed the independent and freethinking Prussian population for Napoleon’s victory rather than their own military miscalculations. They decided they no longer wanted soldiers and citizens who could think for themselves; instead, they wanted submissive people who they could move around like pieces in a game of political chess.

“The goal was to make the bulk of the population compliant servants rather than free individuals who could think for themselves and create and enrich the Prussian culture.”[1]

It was then that the Prussian leaders learned of Robert Owen’s idea to implement a government-run and controlled school system to shape and condition the population. According to Owen’s account, they agreed with the utopists that complete collectivism could only be accomplished through state indoctrination. By 1819, this system of schooling was firmly established throughout Prussia.

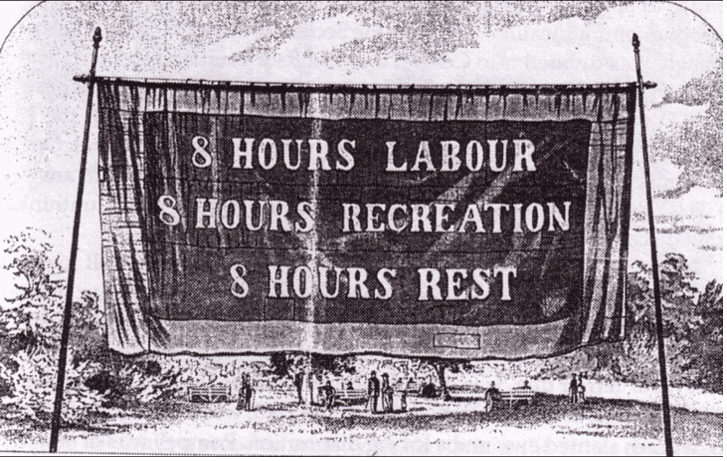

The Prussian model of education segregated the population into three tiers, or “social rank,” based on what education they received:

- Akademiensschulen (Academy schools) prepared students to be future policymakers and leaders. They were taught a wide range of subjects and learned to think critically, write well, read profusely, and strategize.

- Realsschulen (secondary school) prepared the “professional proletariats” to be useful to the upper class. They became engineers, doctors, lawyers, and architects.

- Volksschulen (elementary school), or “people’s school,” taught most of the population to be submissive, passive, and obedient. In practice, they were functionally illiterate and were only taught history that would fuel blissful patriotism.

This was the system that Horace Mann observed in his trip to Prussia. His response to such intellectual atrocities was not to condemn the government for manipulating its citizens and turning the populace into intellectual zombies. Far from it! Instead, he lauded the Prussian government and raced back to America to replicate this system of federal-centric schooling.

Eventually, in 1872, the Prussian government banned all alternative schooling methods, including private schools and homeschooling, according to the Prussian School Inspection Law of 1872. The Law stated, “By annulment of any contrary regulations in individual regions, the supervision of all public and private school and educational institutions is solely under the control of the state.” [2]

“Education of the state, by the state, for the state,” as Alex Newman wrote in his book Indoctrinating Our Children to Death, might be a utopian dream; however, the results it immediately produces are far from heavenly:

- Reduced illiteracy and test scores

- Compulsory tax-funding

- Government-prescribed curriculum

- National testing

- Government-run teacher training and certification

- Students are tracked by vocational and academic aptitudes.

Today, the country of Prussia no longer exists, but it is clear that government schools have long outlasted their founding nation. Indeed, “Deeds survive the doers,” as Horace Mann once wrote. Since 1872, government schools have been producing the same results—dumb populations and government control. With such disastrous results, why did Horace Mann export this failing education reform into his own country?

Horace the Hypocrite

Like Robert Owen before him, Mann was driven by utopian fantasies. He believed that he was responsible for ensuring their implementation in the land of the free by establishing a government school monopoly. For example, he wrote,

“Education…beyond all other devices of human origin, is a great equalizer of conditions of men — the balance wheel of the social machinery…It does better than to disarm the poor of their hostility toward the rich; it prevents being poor.”

This is the message that was paraded around the United States and sold to millions of parents. “Give us your children to raise and train, and we will end world hunger,” seems to be the official slogan of Horace Mann.

Why is it that utopians always steal liberty under the guise of “ending poverty?”

The obvious and immediate challenge to Horace’s statement is if he truly wished for education to be “a great equalizer of conditions of men,” why on earth would he travel to Prussia (a country that was intentionally segregating its population on the basis of education), laud its inherently unequal educational system, and then spend the majority of his professional career working to have it implemented in the United States?

Maybe he believed the public schools just hadn’t been done right yet. Perhaps he truly believed in his mission and really thought children would get the best education in the classroom. You would hope, at least, that Mann would align his own life to the philosophy and schools he mandated for others.

On the contrary! The truth is that Horace Mann refused to send his own three children to a public or “common school,” and instead, he personally homeschooled each of them! Perhaps Horace’s nickname should have been “Horace the Hypocrite.” If he did not believe his own children should go to a public school, why did Mann want them nationalized in the first place?

Horace, the Cynical Reformist

The reality is that Horace Mann feared and distrusted two groups of people: parents and Catholics.

“Horace Mann and his 19th-century education reform colleagues were deeply fearful of parental authority—particularly as the population became more diverse and, in Massachusetts as elsewhere, Irish Catholic immigrants challenged existing cultural and religious norms.” [3]

Because utopians believe it is their responsibility to perfect mankind’s environment and thereby perfect man himself, they cannot trust individual parents to raise their own children because “what if they do a poor job?“

“From a hundred platforms, Mann had lectured that the need for better schools was predicated upon the assumption that parents could no longer be entrusted to perform their traditional roles in moral training and that a more systematic approach within the public school was necessary. Now, as a father, he fell back on the educational responsibilities of the family, hoping to make the fireside achieve for his own son what he wanted the schools to accomplish for others.”[4]

Jonathan Messerli, Mann Biographer

As Mann said, “We who are engaged in the sacred cause of education are entitled to look upon all parents as having given hostages to our cause.” Those “hostages,” of course, are children. Children, who Mann viewed as test subjects in Robert Owen’s case study.

The only thing more terrifying than a parent doing a “bad job” raising their children, in the eyes of Mann and his utopian friends, was Catholic parents raising their children in their faith.

The Massachusetts state legislator commented on the influx of Irish Catholic immigrants, saying, “Those now pouring in upon us, in masses of thousands upon thousands, are wholly of another kind in morals and intellect.” [5]

This was more than a question of “How can we help these people assimilate into American culture?” This was a question of control: “How can a diverse group of people with specific cultures, faiths, and traditions be controlled under one political dogma?” How, indeed?

Robert Owen taught that in order to control a people, you must first control their minds. And so, he instructed his followers, the Prussians and now Mann, to commit themselves to this pursuit of intellectual control.

“To train and educate the rising generation will at all times be the first object of society, to which every other will be subordinate.” — Robert Owen

We must understand that Horace Mann did not have decent motives in imposing government schools on America. He did not believe in the cause. In reality, he was a cynical theorist, hypocritical reformer, and a secret homeschool dad. This is how he ought to be remembered.

The Legacy

In 1848, shortly after his visit to Prussia, Mann resigned as secretary of the Board of Education to take the seat of John Quincy Adams in the US House of Representatives. In 1853, he stepped away from politics for the last time and became the President of Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Here, he spent a lot of his time writing and training his students to further his plans for establishing Prussian education in the United States. You can find his writings here.

While at Antioch, Horace Mann inspired a class of graduates with the words, “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” There is hardly any doubt that, when he died in 1859, Mann believed he had won a great victory for the utopian cause through his American education reform.

Regretfully, for future generations of American children and families, the deeds of the Prussian elites and Horace Mann have outlived them. Even 187 years later, we still live under Horace Mann’s government agency, the Department of Education, which dogmatically and obsessively dictates what millions of children are taught every single day.

Somedays, it can seem that we are inching ever closer to a time when “all public and private schools and educational institutions are solely under the control of the state,” as it was in Mann’s beloved Prussian education system.

But we must not be discouraged because, though the deeds of Horace Mann outlived him all these years, our deeds today can outlive us as well. If we continue to fight for the educational independence we desire and deserve, our children and their children will live to see a day where the government does not raise children and where utopian theories are not imposed on populations; rather, they will live in a free country where true, free-market, God-honoring education flourishes.

Elise DeYoung is a Public Relations and Communications Associate and a Classical Conversations® graduate. With CC, she strives to know God and make Him known in all aspects of her life. She is a servant of Christ, an avid reader, and a professional nap-taker. As she continues her journey towards the Celestial City, she is determined to gain wisdom and understanding wherever it can be found. Soli Deo gloria!

[1] Delphine, R. (n.d.). “The Prussian Model of Education.” STEMiteracy. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://www.stemiteracy.org/the-prussian-model

[2] “School Inspection Law of March 11, 1872.” GHDI, Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=670#:~:text=School%20Inspection%20Law%20of%20March,the%20control%20of%20the%20state

[3] McDonald, K. (2017, May 1). “The Devastating Rise of Mass Schooling.” FEE. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://fee.org/articles/the-devastating-rise-of-mass-schooling/

[4] Messerli, Jonathan. Horace Mann: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972, p. 429.

[5] McDonald, K. (2017, May 1). “The Devastating Rise of Mass Schooling.” FEE. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://fee.org/articles/the-devastating-rise-of-mass-schooling/