By Jane Hampton Cook

Adapted from Key’s correspondence, the story behind the Star-Spangled Banner

The collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key bridge has opened discussions about its namesake. Adapting original sources and letters, I wrote about Francis Scott Key and how he came to write “The Star-Spangled Banner” in my book, The Burning of the White House: James and Dolley Madison and the War of 1812. At the end of this article, I’ve included a notation to give you the historical context surrounding the controversy over two lines in the third verse.

Editor’s note: This blog is published in short. Read the full blog here.

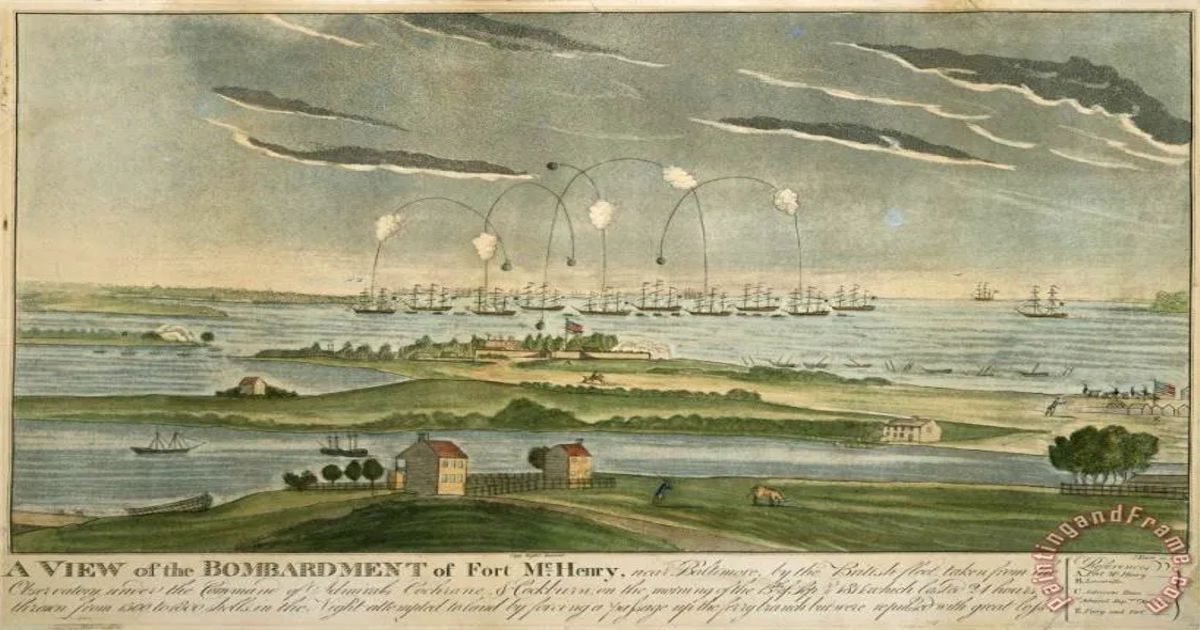

Francis Scott Key, a lawyer who seemed to ponder his place in this world and author of The Star-Spangled Banner, was not pro-war. He was pro-emancipation. Key is credited with writing the Star-Spangled Banner after the 25-hour bombardment of Fort McHenry, which he watched from a British ship with a spyglass.

A series of events led Key and Mr. Skinner to board the British admiral’s ship to secure Dr. Beanes’ release. As it turns out, Key was left out of the discussion that would result in Dr. Beanes’ release. History notes how well the American Army treated the British prisoners of war, and this was a key bargaining chip for Dr. Beanes’ freedom. Interestingly, Key was unimpressed with the British officers.

Key was unimpressed, as he later wrote: “Never was a man more disappointed in his expectations than I have been as to the character of British officers. With some exceptions they appeared to be illiberal, ignorant, and vulgar, and seem filled with a spirit of malignity against everything American. Perhaps, however, I saw them in unfavorable circumstances.” Indeed, he did.

During the attack on Fort McHenry, Key anxiously waited.

“What colors would he see as he placed his eye behind the spyglass and pointed it toward the fort? He didn’t know which was worse, beholding the British Union Jack flag above Fort McHenry or the white flag of surrender. Both would mean victory for the British and capitulation once again from his countrymen.

Suddenly he noticed it. Gone was the American battle flag measuring 17 by 24 feet that had flown over the fort. Instead, he saw the most beautiful colors cast against a canvas of a multi-hue sunrise. The stars and stripes, fifteen of them to represent that nation’s fifteen states that had grown to eighteen by this time, flapped briskly from the fort that morning. The sight could only mean one thing. The Americans still held Fort McHenry.

The flag that Key saw that morning measured 42 feet by 30 feet. It was the largest flag ever flown at a U.S. fort.

On that morning Key saw the larger flag, whose bright stars measured 24 inches from point to point. What he couldn’t have heard that morning was the music at the fort. Because America lacked an official national anthem, the band played the popular Yankee Doodle.”

As he was set from the British ship and sailed back to land, “…his emotion gave way to words, poetic words …”

“O say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light, what so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?”

“Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight” as did the sight of the bombs and rockets. “O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming! And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air.”

“Suddenly Fort McHenry didn’t just represent Baltimore. It symbolized America, as did the 1,000 men who defended it. Suddenly the flag didn’t just soar over Baltimore, it unfurled over the entire United States.”

“O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave, O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

The verses poured from Key’s pen, including lesser-known flourishes that reflected faith:

“O thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand, between their loved homes and the war’s desolation! Blest with victory and peace, may the heaven-rescued land. Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation.” Some were surprising for a man who seemed to oppose the war: “Then conquer we must when our cause it is just, and this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’” Each verse ended with the refrain “and the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!”

“Whether the words flowed easily for Key that day or came to him in bits and pieces to organize into a poetic pattern, one thing is for sure. The result spoke of the emotion that he and so many other Americans felt to learn that they had indeed once again defeated the British.

After the darkness of the burning of the U.S. Capitol and the White House came the dawn brought by the soaring multitude of phoenixes that awakened and defended Baltimore. Hope was brighter than ever. Maybe, just maybe, the Royal Navy would soon abandon America’s shores.”

“Historical context behind the third verse: In recent years, Americans have questioned the meaning of Key’s reference to slavery in the third verse: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave, From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.”

Most of Key’s lyrics are universal, especially in the first verse. The relief of an American victory can apply to Fort McHenry in 1814 and many subsequent victories in American history. The third verse, however, requires historical context to understand what Key meant.

Just a few months before Key wrote these lyrics, the British military had issued a proclamation promising freedom to slaves who would run away. There was a catch, however. The male slaves had to first fight as soldiers in the British army before they could receive their freedom in Canada or the Caribbean.

Key did not think the British army was a suitable place of refuge for slaves or hired mercenaries. By fighting in the British army, they risked both the “terror of flight” and the “gloom of the grave.” Hence, these lyrics are not Key’s opinion justifying slavery but a reflection of the stakes of being forced to fight in the British army.

It also helps, too, to understand why America and Britain were at war in the first place. The primary moral issue behind the War of 1812 was impressment. British sea captains were kidnapping American sailors and “impressing” or forcing them to serve in the British Navy against their will.”

Jane Hampton Cook is a guest contributor to Homeschool Freedom Action Center’s blogs.

Jane Hampton Cook is the author of 10 books, a frequent guest in the national news media, a screenwriter, a former White House staffer, and a former Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission Consultant.