By Elise DeYoung

If history teaches us anything at all, it is that ideas have consequences. Socrates’s ideas prompted his execution, the American ideas freed a nation, and Marx’s ideas killed 100 million people. Indeed, ideas have a cost. Perhaps this is why Scripture consistently warns of corrupt philosophies, bad company, and false teachers. A nation’s teachers have the power to mold its civilization, so some of the most consequential ideas are those believed and taught by educators. Thus, it is our responsibility as free people to keep our educators accountable for the ideas they teach.

Generally, we have failed to do this, and today, our education system is overrun with bad ideas. The consequence of education should be the creation of literate, well-rounded, educated citizens, and the American public school system has failed to do this. This is reflected in the numbers found by The Nation’s Report Card (NAEP):

- 26% of students are proficient in mathematics

- 32% of students are proficient in reading

- 24% of students are proficient in writing

Clearly, we are watching a bad idea unfold before our very eyes. But who promoted this bad idea? What inspired them to do so? Briefly put, government schools were first proposed by a communist utopian named Robert Owens (1771-1858). He believed that, through government-run education, he could condition the masses to accept communism, thereby creating a utopia. The Prussian elites were the first to implement this idea nationwide, and in the early 19th century, they established a harsh education system that outlawed all alternative forms of education. Only a few years later, Horace Mann (1796-1859), inspired by the Prussian government, became the chief advocate of government schools in the United States and established the first Board of Education.

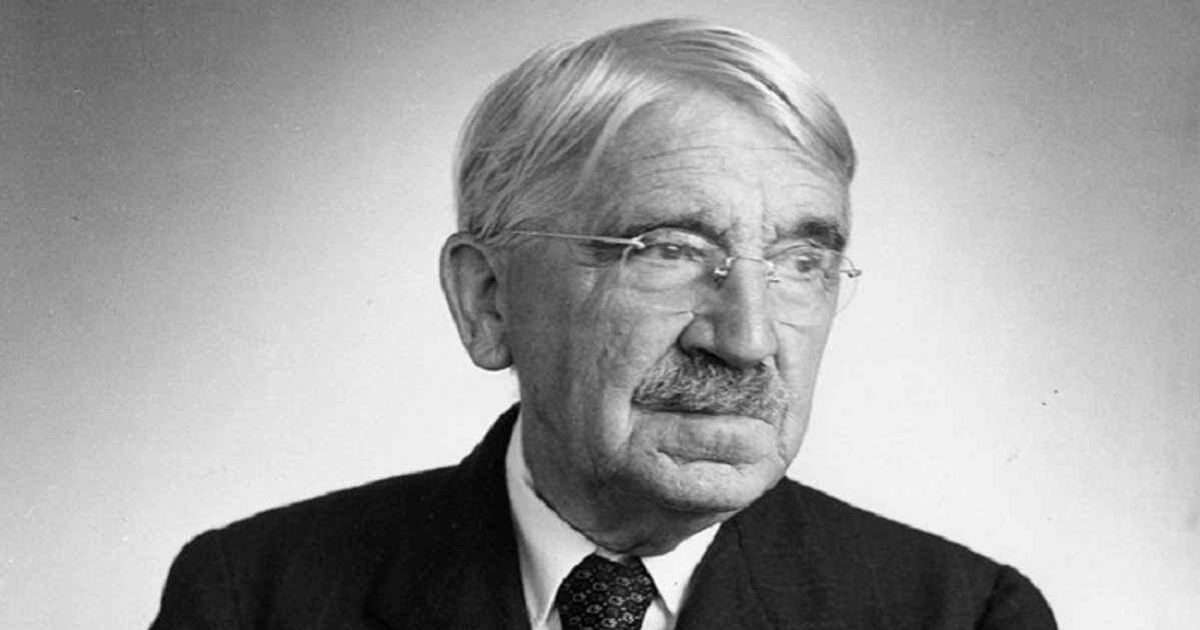

Shortly after Mann’s death, John Dewey entered the government school system. As Dewey grew older and formed his philosophy, he began to view public schools as impractical and oppressive, so he sought to reform the system that had educated him.

Because of his work in philosophy and education reform, John Dewey is a household name in academic circles. His disciples and critics hold two opposite views of him: Advocates of government schools laud John Dewey as a benevolent hero, while public school abolitionists slander him as a bad actor. Whether you believe he was a saint or a Soviet, because of his influence on education reform, we ought to soberly educate ourselves on John Dewey’s life and what he desired to accomplish through education reform. Dewey became known through his own education credentials, academic pedigree, and reform policies.

Early Life and Education

John Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont on October 20, 1859. Even at a young age, Dewey was an excellent student and naturally born teacher. Here is a timeline of Dewey’s college accomplishments and university professorships:

- 1859-1874: Student; Burlington Highschool, Vermont

- 1874-1878: Philosophy Student; University of Vermont

- 1882-1884: Philosophy Doctoral Student; John Hopkins University

- 1884: Assistant Professor; University of Michigan

- 1888: Professor of Philosophy; University of Minnesota

- 1889-1894: Philosophy Department Chair; Michigan University

- 1894: Founder; University of Elementary School at the University of Chicago

- 1894-1904: Philosophy Department Chair; University of Chicago

- 1902-1904: Director of the School of Education, Chicago

- 1904-1930: Professor of Philosophy; Teachers College at Columbia University

- 1930: Retired, Professor Emeritus; Columbia University

With such an impressive resume, it is unsurprising that the Dewey name still carries weight in philosophical circles.

Philosophical Influences

While Dewey was rising in academia, a new scientific discipline was developing overseas. In 1879, psychology emerged when Wilhelm Wundt founded the Laboratory in Leipzig, Germany. Here, Wundt first practiced psychology and taught other educators to do the same. One such disciple was an American named G. Stanley Hall. While Wundt worked to establish the broad practice of experimental psychology, Hall focused his efforts on exploring the development of children. Following his time in Germany, Hall took up a professorship at Johns Hopkins University, where he established the first American psychological laboratory; remarkably, one of his first pupils was John Dewey.

The Premise of Psychology

As Samuel Blumenfeld wrote in his book Crimes of the Educators, the simple premise of Wundt’s psychology was that “Human beings could be studied like animals and could be conditioned to behave as society wanted. Man, in other words, was nothing more than a stimulus-response organism.” This premise sounds outrageous to Christian ears because Scripture tells us that God created man in imago Dei. However, this premise seemed self-evident to secularist thinkers living in the era of Darwinism. Consequently, this idea was at the center of Dewey’s theories. In his book Democracy and Education, Dewey writes extensively about how human behavior is caused by basic biological instinct and that a function of education is to harness that instinct and channel it toward productive social action.

The Tenets of Humanism

Psychology alone did not influence Dewey. Along with the title philosopher, psychologist, and professor, Dewey was a self-proclaimed humanist and one of the first signers of the Humanist Manifesto. A religion with the proud slogan “Good without God,” Dewey quite literally worshipped the idea of perfecting humanity. For example, in the second tenet of Humanism, we read, “Humanism believes that man is a part of nature and that he has emerged as a result of a continuous process.” Once more, progressive evolution is at the center of Dewey’s worldview and belief system.

By understanding Dewey’s view on humanity, we can understand why he focused on reforming education. Like Robert Owen before him, he believed that man was a “creature of circumstance” who needed to be trained like an animal. So, in an effort to further man’s progress toward perfection, Dewey captured the classroom and applied his theories to it.

Education Reform, Human Reform

Robert Owen once said, “To train and educate the rising generation will at all times be the first object of society, to which every other will be subordinate.” John Dewey, it seems, took this mandate as seriously as Robert Owen had meant it. Because he was born into a world that had accepted Owen’s public school, Dewey focused on perfecting the system that was laid out before him.

In his writing, Dewey explored the questions, “What is the purpose of education?” and “How is that purpose best fulfilled?” In Democracy in Education, Dewey considered the former question:

“There is more than a verbal tie between the words common, community, and communication. Men live in a community in virtue of the things which they have in common; and communication is the way in which they come to possess things in common. What they must have in common in order to form a community or society are aims, beliefs, aspirations, knowledge—a common understanding—like-mindedness as the sociologists say.”

He claimed that, in order to last, a society must transfer its shared values and beliefs to the next generation through education.

“The subject matter of education consists of bodies of information and of skills that have been worked out in the past; therefore, the chief business of the school is to transmit them to the new generation. In the past, there have also been developed standards and rules of conducts; moral training consists in forming habits of action in conformity with these rules and standards.”

To put it briefly, Dewey believed education’s purpose is to transmit past generations’ values, information, and skills, and he aimed to discover and establish a method of teaching that would fulfill this mandate. In Experience and Education, Dewey considers the two prominent education methods during his lifetime: traditional and progressive schooling.

Traditional Schools, Progressive Schools

He writes that the purpose of traditional school is “to prepare the young for future responsibilities and for success in life, by means of acquisition of the organized bodies of information and prepared forms of skill which comprehend the material of instruction.” He took issue with “traditional schooling” because he believed it imposed itself on unprepared youth, destroyed the desire to learn, and failed to emphasize practical learning. It must be understood that Dewey was not referring to homeschooling or independent education methods when he referred to “traditional schooling.” Rather, this was his classification of the public school system he had been raised in.

As an alternative to the “traditional schooling” he had experienced, Dewey promoted the benefits of progressive schooling:

“If one attempts to formulate the philosophy of education implicit in the practices of the new education, we may, I think, discover certain common principles amid the variety of progressive schools now existing. To imposition from above is opposed expression and cultivation of individuality; to external discipline is opposed free activity; to learning from texts and teachers, learning through experience; to acquisition of isolated skills and techniques by drill, is opposed acquisition of them as means of attaining ends which make direct vital appeal; to preparation for a more or less remote future is opposed making the most of the opportunities of present life; to static aims of materials is opposed acquaintance with a changing world.”

Dewey wanted to create a system of schooling where learning was subjective, experience was valued above lecturing, and practical skills were cultivated. He believed that through education reform, humanity could be reformed to be well-equipped, useful citizens ready to fulfill social duties.

The Consequences of Dewey

John Dewey believed his ideas would create the best future for American education, but have they? A nation is shaped by its educators, and for over one hundred years, millions of Americans have given up their children as test subjects in the largest education experiment in history. It is time to seriously consider the real consequences of Dewey’s education reform. In this series, we will consider John Dewey’s role in creating the literacy crisis in our nation, introducing humanist teaching in the classroom, and redefining the purpose of education.

It is time for Americans to take a serious and sober look at the ideas of the man known as the father of progressive education. Only through a proper understanding of John Dewey and his ideas can we correct the consequences in every public school classroom around the United States.

Elise DeYoung is a Public Relations and Communications Associate and a Classical Conversations® graduate. With CC, she strives to know God and to make Him known in all aspects of her life. She is a servant of Christ, an avid reader, and a professional nap-taker. As she continues her journey towards the Celestial City, she is determined to gain wisdom and understanding wherever it can be found. Soli Deo gloria!